eternal woodstock

pretending to moving on to avoid the fact that you have to actually move on

Around 1993, the internet entered a period known as Eternal September. The flipside (Temporary September?) refers to an annual spike in new internet users gaining access via their colleges at the start of the fall semester, and subsequently not knowing how to behave. But starting around September 1993, people started coming online all year round, similarly not knowing how to behave — a year-round influx of newbies of all ages and myriad backgrounds. This period of constantly having to deal with new users who don’t know what they’re doing or who they’re talking to has been ongoing for the last three decades.

I am reminded of this “Eternal” concept because earlier this year, I read Jimmy McDonough's Shakey, a really amazing biography of Neil Young. Pretty much every part of it is wildly illuminating and funny and sad, and you really get the impression that Neil Young is one of the great weirdos of all time. There are a bazillion interesting details in the book. One of my favorites is a passage about Woodstock, which Young played as part of CSNY:

“A bunch of dopes in the mud not even paying attention,” said Richard Meltzer of Woodstock. He left on the first day. “Woodstock was just the first time the middle class got hip to the whole rock scene. By the time you had that many people doing it in one place, it was closer to an Alan Freed show … it was minus the sixties consciousness. It was just entertainment value.” Ken Viola, also present, was similarly disenchanted. “As a communal event it was a big success. But I remember being at Woodstock and saying, ‘It’s over.’”

And The New York Times’s Jon Pareles on the occasion of Woodstock’s 50th anniversary:

Most importantly, the scale of Woodstock showed people who had considered themselves “freaks” that they weren’t as small a minority as they had thought. Robin Williamson of the Incredible String Band paused during a tuning break to marvel, “The thing that surprises me is, like, how many of us there are. And it makes me fantastically happy.”

For those who were coldbloodedly watching numbers, even in 1969, Woodstock simply identified a big, promising segment of the youth market, ready for the commercial exploitation that would ensue almost immediately. “Woodstock Nation,” despite Abbie Hoffman’s hopes when he coined the term, turned out to be a demographic rather than a political force.

Huh! That's kinda interesting to me, as someone who was not able to attend Woodstock (was not born yet; I'm very youthful) and who only really knows of it through cultural osmosis as the ultimate hippie event. All the rock stars showed up to play some cool songs for flower-crowned, mud-covered hippies, and nobody got beaten to death by a motorcycle gang. Woodstock, I had previously thought, was in the elite tier of cool sixties events.

And yet, here's guys who were there, quite literally proclaiming that, "It's over."

I’ll get back to Woodstock in a second.

Yesterday, Meta launched Threads, which is a feed-based social media service where users type text into a box, and then see the text they typed as a post on their screen. Posts can be viewed in a scrollable “feed.” This may sound familiar to you. It is, at least, the sixth Twitter-like thing that people have tried to use to recreate Twitter since that company started its slow descent into really funny incompetence.

Previously there was:

Mastodon. Like Twitter, but just as cumbersome in different ways. Made people start using the term "fediverse" even though none of them could define it if their life was at stake.

Cohost. Kinda like a combination of Twitter and Tumblr. I like it overall, but it was never gonna replace Twitter no matter how badly anyone wanted it to. This may be intentional.

Post.News. Nothing much to say except it’s lame and sucks and will die soon.

Hive. Built by just a couple of guys. Shut down briefly, shortly after a debilitating influx of users, to address a security issue. Haven't heard about it since.

Substack Notes. Like Twitter, but only for heterodox freakos and media expats with PTSD (and me — the one cool, normal guy). Substack’s leadership is somehow unable to say "We don't condone racism" in a way that seems like a child has afflicted them with some sort of Liar Liar-type birthday wish. This is not not concerning.

Bluesky. Maybe the most viable of these simply based on buzz alone. Much like TikTok, it got a lot of attention for its “good vibes” even though it seems to have quickly given way to niche drama infighting. "Thank you for making this thing that's like Twitter but without the problems!" the users tell the very small team making Bluesky, "but we are now going to speedrun reinventing those very problems." Also, you need an invite to join. As for whether the invite-gating tactic will be successful in the long run, I’ll just note that I have not read an article on Medium in at least two years and Clubhouse laid off half of its employees earlier this year. (I think the coolest part of Bluesky is the way that it uses domain names as handles. It's a novel way to apply open web standards and one of the true ways of owning a part of the internet to more modern social-media use cases.)

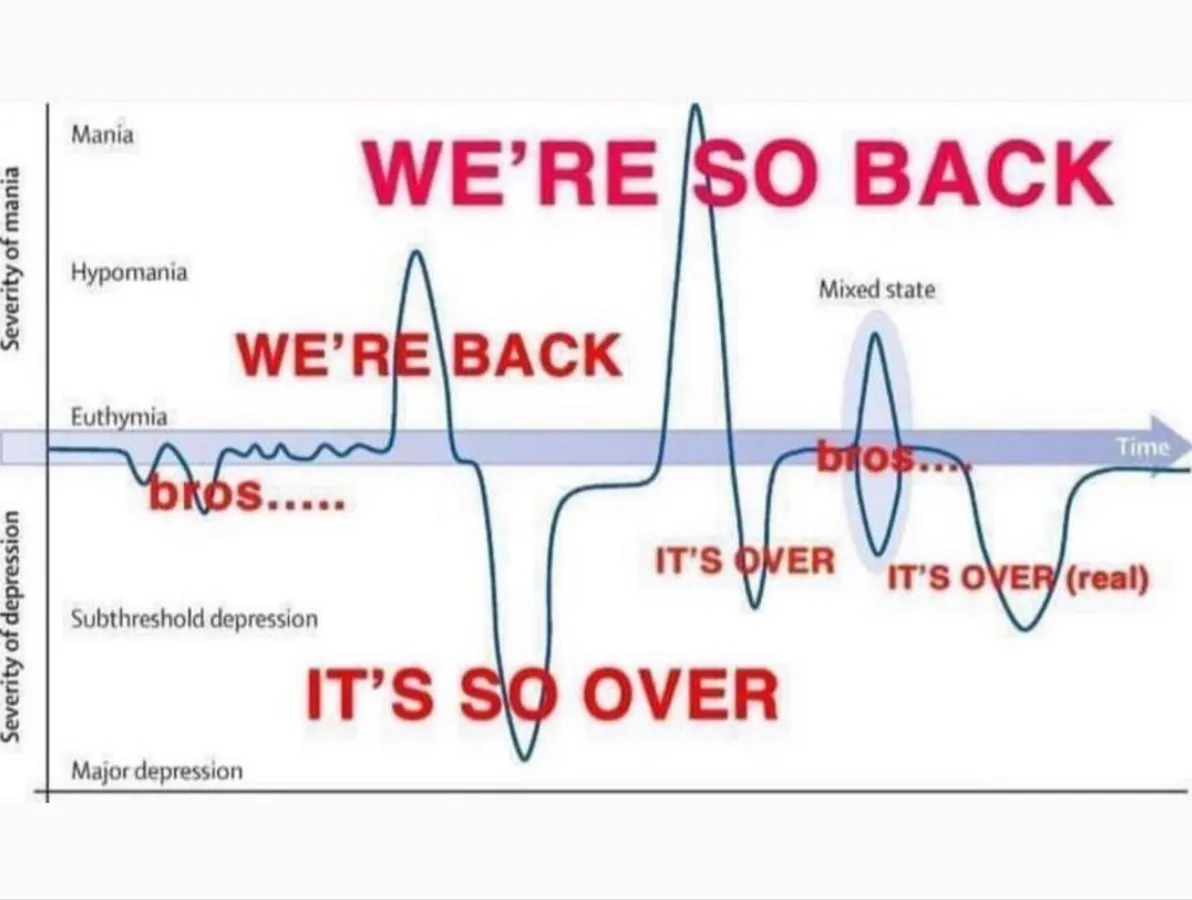

As people keep trying to make Twitter 2 happen, we are now in a period that I'm calling Eternal Woodstock — every few weeks, users flock en masse to new platforms, rolling around in the mud, getting high on Like-dopamine, hoping that they can keep the transgressive, off-kilter meme magic going just a little longer, even though social-media culture already been fully hollowed out and commercialized.

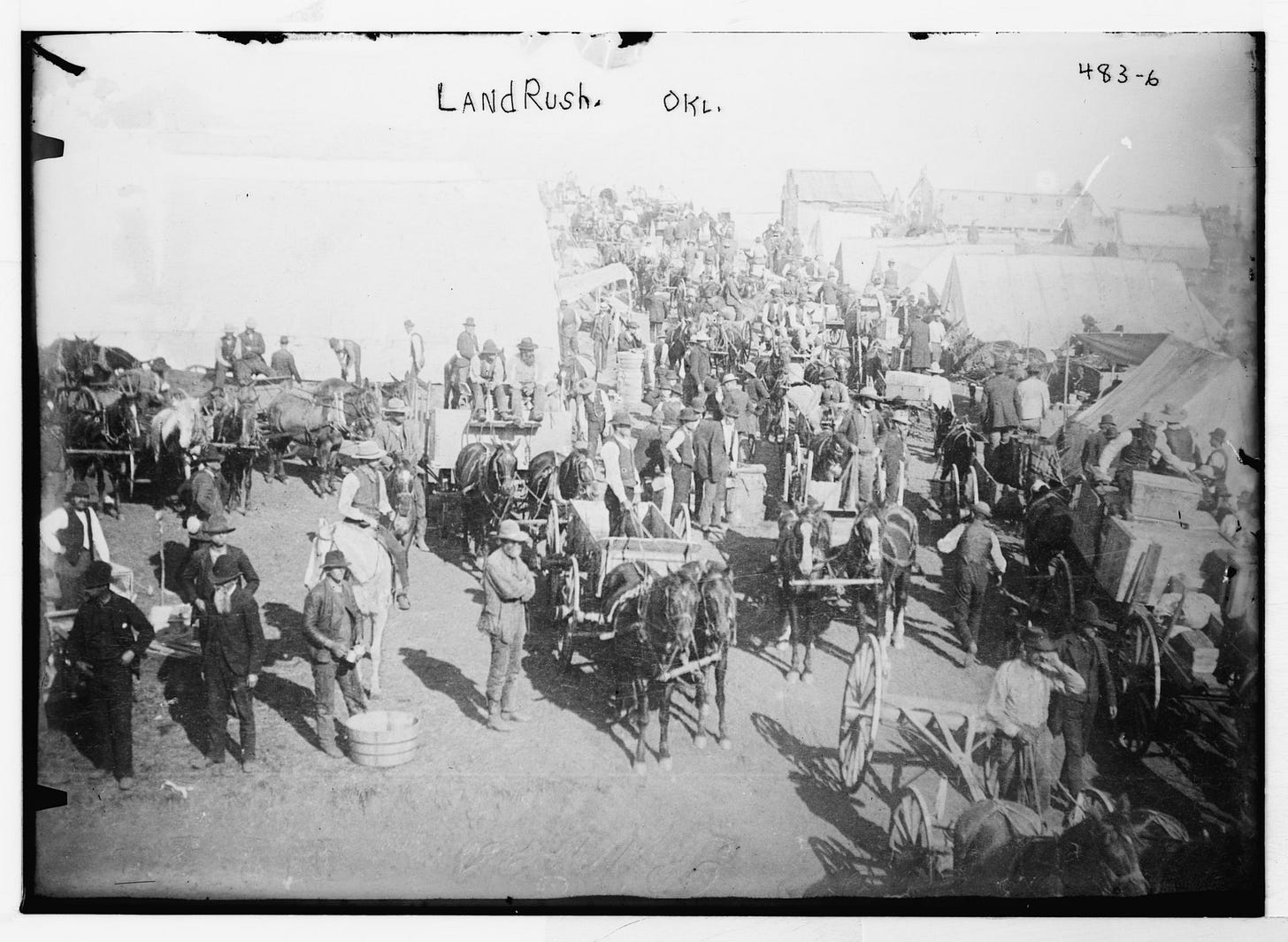

In addition to Woodstock, the other historical event that this moment in internet history reminds me of is the Land Rush of 1889. On April 22 of that year, the U.S. government (after clearing Native Americans out of the territory that would eventually become Oklahoma City) held a “first come, first serve” event for settlers. A gun went off at noon, and then settlers rushed in to claim their own patch of land in a chaotic, unorganized, and sometimes violent squabble. In half a day, a city of thousands suddenly sprang into existence.

A similar event is happening on the Twitter-alikes, but the “land rush” is not really about claiming a username, as has been the case in the past. Instead, it’s about maintaining a presence in the feed.

On Bluesky, the land rush is in a feed called What’s Hot, whose determining algorithm has changed over time. For a while, getting 12 likes on a post would earn it placement in What’s Hot, and so users intent on being early and appearing like a big account flooded the zone. They followed a zillion people and posted recycled memes so that getting 12 likes became trivial, or they made sure they built an affinity circle to achieve the same result. The implied idea seemed to be that a new user would look at the feed and think, “This user must be important if they’re on What’s Hot. I simply must follow!” (The determining factors for What constitutes Hot have since changed, and Bluesky has since rolled out the ability for users to create their own algorithmic ranking systems.)

The same phenomenon is happening on Meta’s Threads Similar to What’s Hot and Tiktok’s For You, fighting for real estate on the feed at a platform’s moment of inception is crucial. On Threads, an opaquely ranked algorithmic feed full of “verified” (meaning “blue-check’d”) celebrities and public figures, and — very, very occasionally — posts from people you actually follow and want to see. Threads gives you the illusion of control and then shovels you pretty much exclusively crap. This is by design, because Meta gave the big verified accounts access before anybody else and allows users to import their Instagram follows, in effect producing a brand-friendly Big Bang. This is a remarkably craven move, and most indicative of where this is all heading. Anyone loading up Threads for the first time will be greeted with an illusory barrage of empty engagement-bait garbage from celebrities, influencers, and Tequila-hawking meme accounts they follow; accounts that do not actually care to hear from the riff-raff. Threads is not a platform full of ads, but something far more terrifying: a platform full of users who have voluntarily sold out.

Luckily, it won’t last. Ultimately, the pressure of being “Twitter-like platform that’s not actually Twitter and has learned from Twitter’s mistakes” comes with an implied assumption that this activity will allow Threads or Bluesky or Mastodon to scale up with minimal issues. The sense I get from the chatter of Bluesky’s What’s Hot and Threads’s day-one glurge is that people want all of the benefits of Twitter (cool stuff user didn’t even know they wanted, funny jokes, someone they don’t like getting insulted) with none of the downside (stuff a user doesn’t want, bad jokes, getting insulted oneself), despite the fact that both of these poles are made possible from one thing: the sheer size of the userbase. The Threads ethos right now — much like the other Twitter 2 land rushes before it — is a contradictory mixture of earnest online community building and craven creator-brained growth hacking. Based on the events of the last decade, we already know which of those competing impulses will win out.

“Look at how ideologically aligned and positive this platform feels! Let’s keep it that way forever as we feverishly try to scale up and get billions of other users on board. It’s never worked for any other online platform… but it might work for us.”